“There are three kinds of lies, lies, damn lies, and statistics.” – attributed to Benjamin Disraeli, British Prime Minister (1868)

Oliver Marcell (1895-1949) lived long enough to see baseball integrated and a trickle of Negro Leagues stars enter Integrated Professional Baseball. He was nicknamed “Ghost” with two theories offered up for his moniker. The less likely was a product of his personality, that of a loner. He rarely socialized with his teammates preferring to spend time in gambling dens and in the company of ladies of the night. As a result, he did not travel with his teammates from game to game. Instead, he would show up in time to suit up with no explanation of how he arrived at the next destination, appearing as an apparition to his teammates.

The more likely explanation is due to his catlike reflexes at the hot corner. Marcel is said to have played 10 feet closer to home plate and 10 feet farther away from the third base line than anyone else. With his amazing reflexes, he was still able to field hot liners hit directly at him or down the line that seemingly were headed for a double. By playing so close to home plate, he may well have intimidated batters and taken away the bunt, a staple of Negro Leagues play.

During the time of Marcell’s career, third base was primarily regarded as a position filled with defensive wizards. It is the least populated field position in the National Baseball Hall of Fame with only 17 members. Eddie Mathews (1952-1968) who was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1978 is generally regarded as the prototype of the modern, power-hitting third baseman. All third basemen whose careers preceded Mathews and were elected to the Hall were defensive specialists first and foremost. An exception can be made for Negro Leagues great Jud “Boojum” Wilson, elected to the Hall in 2006, who showed more power than most third basemen, but not nearly to the level of Mathews. Wilson also only played 45% of his games at third. Judy Johnson (1975) and Ray Dandridge (1987), the two other Negro Leagues third basemen in the Hall had more limited power, but were considered defensive wizards with high batting averages.

But the mystery of the ghost is not just how Marcell received his nickname, but why he does not have a plaque in Cooperstown despite being highly regarded and being selected as the starting third baseman in the famed 1952 Pittsburgh Courier poll above Dandridge, Johnson and Wilson. For those of you not familiar with this poll, by 1952, the Negro Leagues had all but ceased to exist. Modern standards bookend the Negro Leagues between 1920-1948. The 1952 poll was meant to preserve the memory of the great players of the Negro Leagues as a Dream Team. Two teams were announced along with a “Role of Honor.” Each team consisted of 19 players – seven pitchers, three utility players, a back-up catcher, and eight position players. The results announced in the April 19, 1952 edition of the Pittsburgh Courier list vote totals for the first team, a second team with partial vote totals, and a Roll of Honor. The 31-member panel of voters[1] was a knowledgeable group of former players (21), Negro Leagues executives (5) and sports writers (5). Their careers spanned the entirety of the Negro Leagues.

At third base, Marcell received 16 votes, over half, as the starting third baseman. Judy Johnson was listed as the second team selection and five men –Jud Wilson, Ray Dandridge, Dave Malarcher, Bill Francis, and Jim Taylor – are listed on the Roll of Honor in that order, although no claim in made that this reflects their vote totals. An excellent analysis by J. Fred Brillhart (https://johndonaldson.bravehost.com/pdf/00237.pdf) demonstrates Johnson, as the second team selection, could have had at most 10 votes. The text of the Pittsburgh Courier article states, “THIRD BASE honors were taken by Oliver Marcell (Lincoln Giants and Bacharachs) who could do EVERYTHING! A fielding gem, who could go to his right of left with equal facility, could come up with breath-taking plays on bunts…who was equally good at laying one down or going for the long ball, he was a ball player’s delight and the idol of fandom.”

This description, with an emphasis on his fielding skills, supports defense as the primary reason Marcell was selected. While other positions mention defensive abilities (Buck Leonard “smooth fielding, accurate throwing to bases[2]”), none does so to the extent of Marcell. The description also supports the fielding legend of his nickname. Numerous newspaper articles over the course of his career sung his accolades such as the Brooklyn Citizen on April 26, 1926 calling him, “the classiest third sacker in colored baseball.” As early as January 10, 1925, columnist William E Clark of the New York Age named Marcell to his All-Time All-Star team at third. Judy Johnson said Marcell was worthy of first team honors and noted that when they played together, it was Johnson who moved to second base leaving Marcell to guard the hot corner. Both Oscar Charleston (1949) and John Henry “Pop” Lloyd (1953) named Marcelle to their All-Time All-Star team at third base.

However, in the analysis of his personality, it may stray from the truth in an attempt to not speak ill of the (recently) departed. Marcell has passed away less than three years earlier and his son, Ziggy, was recently active in both Negro Leagues and Minor Leagues baseball and semi-pro basketball where he had been a teammate of Jackie Robinson on the Los Angeles Red Devils.

Ghost Marcell had a reputation as a hard-drinking, violence prone, womanizing man with a hair trigger temper who found his way into numerous scraps with players, fans and the law. His most noteworthy were when he was questioned in the shooting death of Benjamin Adair, in an apparent drug deal gone sour. Adair was shot by Dave Brown on April 28, 1925. Teammates Frank Wickware and Marcell were with Brown when the incident happened. Brown disappeared and was never found (more on that story another time). Marcell and Wickware were released after questioning. He once hit teammate Oscar Charleston in the head with a bat. His career ended as a consequence of another fight. In 1930, he got into an argument over a gambling debt with teammate Frank Warfield. During the scrap, Warfield bit off a piece of Marcell’s nose. Marcell was handsome and proud. For the short remainder of his career, he played with a patch covering his nose and was subject to brutal hazing by fans which along with excessive drinking hastened the end of his career. If he was a fan favorite, contemporary newspaper articles do not mention it. He appears to be a man you approached with caution for fear of triggering that infamous temper.

It is really no mystery why Marcell was granted first team honors in the 1952 poll. Despite a difficult personality, his contemporaries, executives and sportswriters agreed he was the best at his position. Marcell came out on top of more than half the ballots cast. Among position players, only Josh Gibson (23 votes) at catcher and Oscar Charleston (20) in centerfield received more votes than did Marcell. Only two pitchers finished with more than half the possible votes – Smokey Joe Williams (20) and Satchel Paige (19). Marcell kept elite company.

What is more of a mystery is why is he not in the Hall of Fame when every other first team player[3] is except for pitcher John Donaldson and utility infielder Sam Bankhead are? Both Donaldson and Bankhead are often in the conversation of who should be among the next Negro Leagues players to enter the Hall, but Marcell is not. Marcell also finished ahead of three future Hall of Fame inductees at his position – Dandridge, Johnson, and Suttles.

As previously indicated, Marcell was not a player you would want as a neighbor. He did not attain respect through the warmth of his personality. Given the breadth and experience of the Pittsburgh Courier panel, there does not appear to be favoritism that outweighs performance with one notable exception, Jackie Robinson. Robinson’s selection as the first team second baseman is understandable, but also an example of sentiment over performance. Robinson played only one partial season (1945) in the Negro Leagues consisting of 35 games for which we have box scores. However, by 1952, he had integrated baseball, won the Rookie of the Year honors (1947), an MVP award (1949), and had been selected to four National League All-Star teams. It was his post-Negro Leagues career that earned him a spot on this team as was acknowledged in the text of the article reporting the poll results.

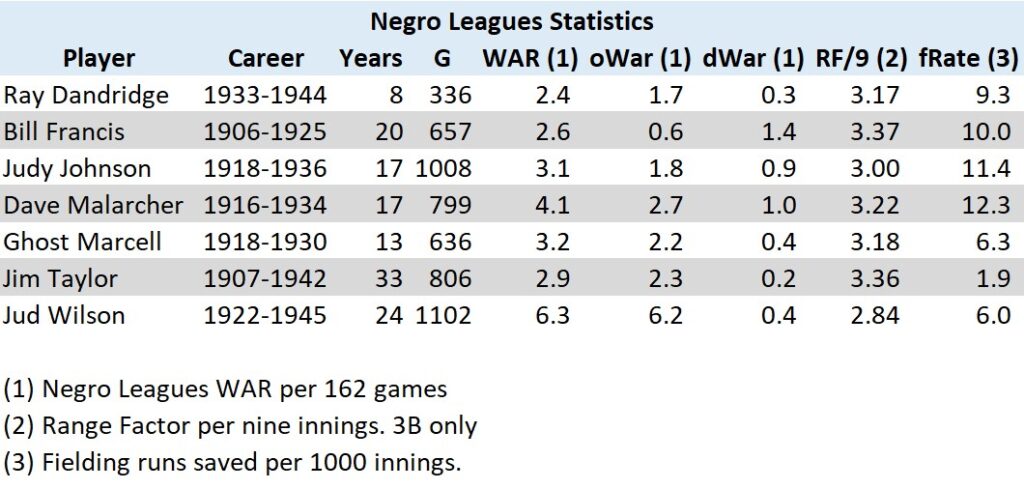

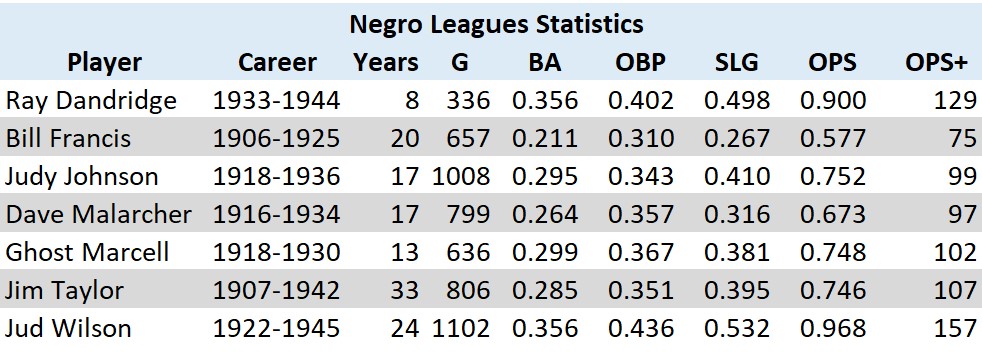

This writer thinks Marcell was short-changed by the delay in voting Negro Leagues players into the Hall. By the time he was considered, Sabermetics held sway over eyewitness accounts. When we look at the field of players voted upon for third base with the hindsight of Sabermetrics, Marcell does not stand-out either defensively or offensively. The experts who watched him play saw some intangible skill not captured in these statistics. Perhaps he took away a significant portion of the field from batters forcing them to hit the ball where they did not want to between shortstop and first. Those statistics then show up in the records of others. The voters in 1952 did not have access to modern Sabermetric statistics and compiled career totals were probably non-existent. So, they had to rely on memory, hot stove league conversations, and the feeling of who were the players that were most likely to help a team win.

All statistics are courtesy of seamheads.com

Marcell is a good example of the conflict between baseball acumen and Sabermetrics. In many polls, Marcell was selected as the starting third baseman on Negro Leagues All-Time All-Star teams, but when statistics were compiled and analyzed, he appears undistinguished. This brings to mind a paraphrase of Chico Marx’s line in the movie Duck Soup, “Who are you going to believe, statistics or your lying eyes?”

The men who lived the Negro Leagues believed their lying eyes. Maybe we should as well.

[1] Executives: Lloyd Thompson, Tom Baird, Eddie GottLieb, Syd Pollack, Abe Saperstein; Players: Cool Papa Bell, Jimmie Crutchfield, Frank Forbes, Judy Johnson, Dave Malarcher, Bill Pierce, Chaney White, Larry Brown, Dizzy Dismukes, Vic Harris, Fats Jenkins, Jack Marshall, Jake Stephens, Bobby Williams, Oscar Charleston, Bunny Davis, Jesse Hubbard, John Henry Lloyd, Ted Page, Willie Wells, Bill Yancey; Sportswriters: Dan Barley (The New York Amsterdam News), Alvin Moses & Ric Roberts & Dr. Rollo Wilson (Pittsburgh Courier), Fay Young (Chicago Defender)

[2] Not to take anything away from Leonard’s rightful selection, but how often is the stature of first basemen tied to their throwing ability?

[3] On the second team, seven of the 19 players selected are also in the Hall of Fame as are nine members of the Roll of Honor.

[1] Executives: Lloyd Thompson, Tom Baird, Eddie GottLieb, Syd Pollack, Abe Saperstein; Players: Cool Papa Bell, Jimmie Crutchfield, Frank Forbes, Judy Johnson, Dave Malarcher, Bill Pierce, Chaney White, Larry Brown, Dizzy Dismukes, Vic Harris, Fats Jenkins, Jack Marshall, Jake Stephens, Bobby Williams, Oscar Charleston, Bunny Davis, Jesse Hubbard, John Henry Lloyd, Ted Page, Willie Wells, Bill Yancey; Sportswriters: Dan Barley (The New York Amsterdam News), Alvin Moses & Ric Roberts & Dr. Rollo Wilson (Pittsburgh Courier), Fay Young (Chicago Defender)

[1] Not to take anything away from Leonard’s rightful selection, but how often is the stature of first basemen tied to their throwing ability?

[1] On the second team, seven of the 19 players selected are also in the Hall of Fame as are nine members of the Roll of Honor.