by Jay Caldwell

In ancient Greek mythology, four pillars held up the sky. If one looks at the Negro Leagues firmament, four pillars (teams) held up the Negro Leagues. The city of Chicago was home to the first great dynasty with the Chicago American Giants led my Andrew “Rube” Foster. Foster established the Negro National League in 1920 and dominated it for its first four seasons while plotting a path for sustained excellence. His frenemy, Ed Bolden, rebelled against Foster and sought his own, independent path in the East for his Hilldale Club, a worthy successor to the dominant Philadelphia Giants at the turn of the 20th century. These two teams dominated the early years of organized Negro League play. As Bolden’s brainchild, the Eastern Colored League, was ripped asunder, the center of play in the east moved 300 miles west to the industrial city of Pittsburgh. Gus Greenlee’s brand of checkbook ownership eclipsed the early dominance of Cum Posey’s independent Homestead Grays (1921 – 1931). The Pittsburgh Crawfords (1932-1936) quickly rose fielding some of baseball’s best teams before succumbing to the influence of a checkbook player, Leroy “Satchel” Paige, who lured half of the Crawfords to the Dominican Republic in 1937 based on the guarantee of a one-time fabulous payday. With the Crawfords devastated, the slow and steady Posey reclaimed the title of Beast of the East for his Homestead Grays who dominated Eastern Negro Leagues baseball from 1937-1948.

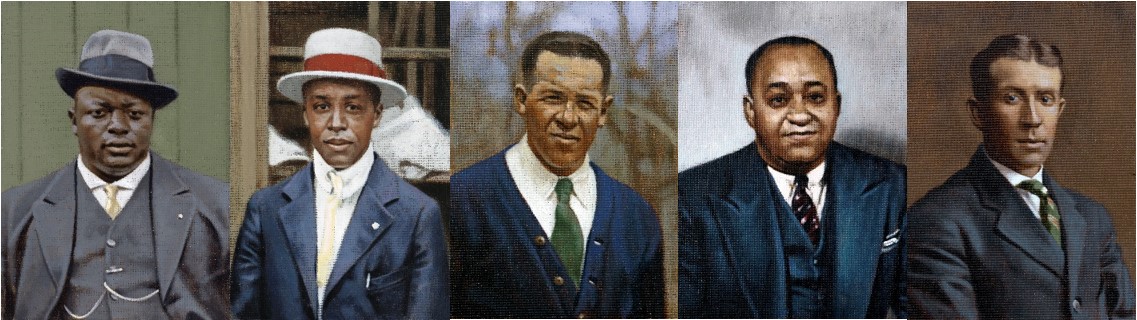

Andrew “Rube” Foster, Ed Bolden, Cum Posey, Gus Greenlee, and J.L. Wilkinson. Paintings by Graig Kreindler

But, as in Greek mythology, the true Atlas lies on the western most horizon, not in the Mediterranean Sea, but in Kansas City. J.L. Wilkinson’s Kansas City Monarchs were the dominant team throughout the course of Negro Leagues baseball (1920-1948) and for several years both before (All Nations) and beyond. Throughout his tenure, Wilkinson fielded a variety of stars beginning with Bullet Rogan, José Méndez, and John Donaldson, who give way in the 1930s to Chet Brewer, Willard Brown, Hilton Smith, and who, in turn, passed the mantle on to Satchel Paige, Buck O’Neil, Jackie Robinson, Elston Howard, and Ernie Banks.

As players shuffled in and out, the popular and respected Wilkinson was a constant owning the team from 1920-1948. Tom Younger Baird was a minority owner during Wilkinson’s tenure before taking full control from 1948-1955. But Baird never had Wilkinson’s rapport with the players possibly because rumors of his membership in the Ku Klux Klan were true. Excluding the owners, the longest tenured employee who combined both physical and psychological therapy and contributed to the sense of pride and oral history connected Rogan to Howard for the entire Monarchs run as a major league team was Frank James “Jewbaby or Jew Baby” Floyd.

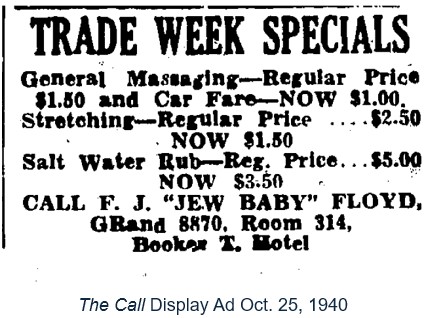

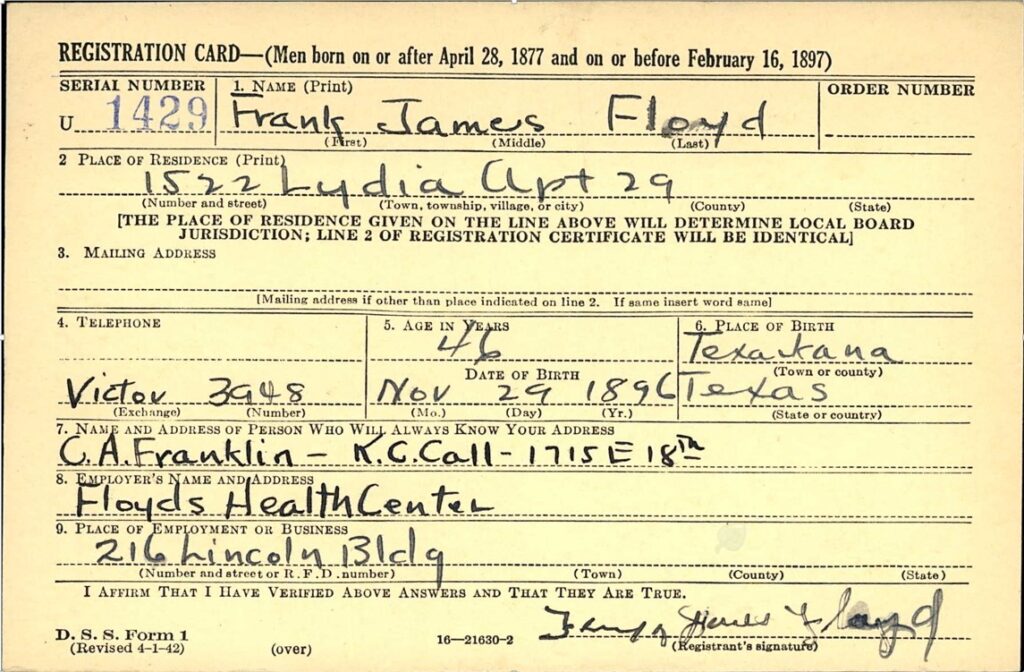

Floyd was born in Texarkana, Texas on November 29, 1896. The first thing people tend to ask is, “Why is a Black Christian called Jew Baby?” The Kansas City American reported on July 4, 1929, “An ardent white lady fan dubbed the elongated gentleman with this name…who, by the way, does posses a facial appendage resembling somewhat the Hebrew variety…” “Jew Baby” was a typical, if not common, nickname for non-Jewish people. In addition to Floyd Negro Leaguers George Bennette and Mex Johnson shared the nickname. History has obscured the thought process behind this practice which sounds demeaning to our modern ear, but it may have originated from the Christ child being an olive complexioned Jewish baby, not a Northern European as often depicted. The nickname “Jew Baby” appears to apply only to Black males. Whatever its origin, Floyd did not appear to be offended by the nickname and he was commonly called Jew Baby by both his friends and the admiring press. He also used it himself in advertising his services in local newspapers.

Floyd’s journey to Kansas City is murky. Some early accounts have him pitching for the Waco (TX) Yellow Jackets and joining fellow Texan, Hurley McNair, as a pitcher on Wilkinson’s All Nations team. This would place his arrival in Kansas City as early as 1917 at age 20. However, extensive research by Peter Gorton of the John Donaldson Network has not uncovered any box scores or articles involving Floyd with either the All Nations or Monarchs until 1923.

Floyd first appears by name in the February 9, 1923 edition of Kansas City’s Black newspaper, The Call. The Call referenced “Jew Baby” as a contributor to the Winter Stove League at Stark’s on the corner of 18th and Vine, close to the present location of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. This implies he was already well known in Black baseball circles. Visually he appears in the photo upon which this painting is based taken on October 11, 1924, at the opening of the Negro Leagues World Series at Muehlebach Field in Kansas City.

The Call next referenced Floyd in a tongue-in-cheek piece on April 3,1926 when discussing the Monarchs chances for the upcoming season and concluded their assessment stating, “Only one fly in the ointment – our old friend, “Jew Baby” Floyd trainer extraordinary. He’s wearing a new set of glad rags and the police aren’t looking for him. One of two things must have happened – he’s either struck oil or he’s running with the opposition. All he’d have to do would be to put a little more of anything in that mixture he uses on ball players arms and legs- and the Monarchs would be lucky to finish at all. It’s made by him, which is a rap for it right off the reel. It’s been rumored he’s been writing letters to Rube Foster this spring. An investigation is in order.”

In this same vein, The Call reported on preparations for spring training on April 1, 1927, “As for their physical ailments— more arms, legs and even heads—”Jew Baby” Floyd, the official trainer, will take care of them. Charley horse or stomache [sic] ache, its [sic] all the same to Jew Baby. He’s got a dirty little bag he carries and in that bag are some nasty little concoctions that were handed down to him from his swipe[1] ancestors of the male gender, for use on horses. Since horses are becoming passe, Jew, rather than waste all this knowledge, steamed the “For Horses” labels off the bottles and pasted on them “For Ball Players.” And until it kills some of them he will continue to rub it on. He gets a rep solely because the stuff is so strong it makes

[1] In horse racing, a swipe is a person who grooms horses.

the patient forget what his original ailment was. Oh yes, “Doctor Jew Baby” will really take care of them.”

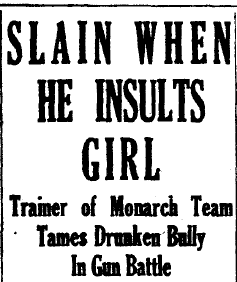

While Jew Baby was the Monarch’s full-time trainer, traveling with the team on the road, it was still a part-time job requiring he find additional work as did the ball players themselves. Several articles refer to his work as a trainer with the All Nations, and professional hockey teams including the St. Paul Saints (1925-1930), the Kansas City Greyhounds (1933-1940), the Kansas City Americans (1940-1942). In one ad from 1941, he was pictured administering to Bill Nutt, the Americans’ goalie. Floyd also worked at Frank Banks colored soft drink and sandwich parlor at 1610 East 18th Street. According to the January 31, 1930 edition of The Call, Floyd was working one morning around 1 AM when a drunken, White bus driver by the name of Ray Wilson came in for food. Wilson “grabbed [the Black waitress on duty], patting her offensively.” Floyd intervened asking Wilson to stop, remonstrating that a Black man would be lynched if he entered a White establishment and handled a White waitress in similar fashion. Wilson left, but owner Banks was sufficiently alarmed that he called the police for help. Kansas City’s finest arrived, but after a two-hour wait had to move on. Finally, Wilson returned around 3:45 AM brandishing a gun. Wilson got off four shots, two in Floyd’s direction before Floyd returned fire with his own gun killing Wilson. The results of a court hearing held on February 8th were not published, but Floyd appears to have been acquitted on grounds of self-defense. The Call later quotes Floyd that month on the Monarchs prospects for the upcoming season.

According to the 1930 U.S. Census, Floyd listed his occupation as a waiter on the railroad. The Great Depression had just started the previous fall and Floyd may have been working multiple jobs. The census listed his address as 1122 E. 23rd St. in Kansas City, a bare ¾ of a mile from the Monarchs’ home at Muehlebach Field.

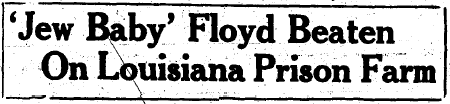

Floyd continued his duties with the Monarchs in relative anonymity, being quoted on occasion about the physical condition of the club. This period of quiet ended on Saturday April 10, 1937, during spring training in Shreveport, LA. According to The Call (April 30, 1937), Floyd stationed himself beyond the outfield fence to retrieve baseballs hit beyond the field’s boundaries as was common in the day. Two White boys aged 13 and 16 refused to give him the balls they had picked up. One of the boys ran home to fetch his father who upon coming to the park said, “Come here, n——. What do you mean by taking that ball from my kids? You know we generally lynch n——s down here when they try to boss white folks.”

The father tried to haul Floyd away, but J.L. Wilkinson, alerted by the abusive language, came to Floyd’s temporary rescue, and summoned a police officer to arrest Floyd rather than allow an irate citizen to take him. Wilkinson got Floyd released on a $50 bond and paid $20 for a lawyer thinking that was sufficient to get Floyd back to Kansas City with the Monarchs. Wilkinson had pressing business in Houston and was unable to stay for the trial. On Monday April 12, the boys told the judge Floyd pulled a knife on them and threw rocks at them. The judge, who did not allow Floyd to testify, convicted Jew Baby and fined him $50 for disturbing the peace and $150 for assault. Unable to pay the fines, the judge sentenced Floyd to 90 days incarceration at the municipal prison farm where he began picking potatoes.

On Wednesday April 14, Floyd reported sick claiming his throat was constricted. According to Floyd, the prison guard stated, “I hope it does close up on you. It’ll make you wish you were dead.” The guard then began thrashing Floyd with a large tree limb. Floyd worked in the fields another day before a doctor confirmed his throat ailment. It took until Monday, April 17, before Wilkinson was informed of Floyd’s situation and was able to wire $225 to win Floyd’s release. Floyd returned to Kansas City with evidence of the beatings he endured and vowed that he would stay with the Monarchs but would not travel south for spring training again.

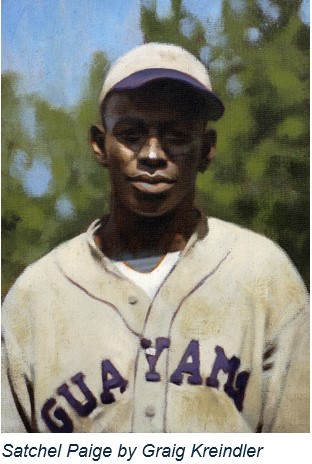

Floyd’s best-known work was on the horizon. People forget that the Monarchs’ most legendary player was a veteran of 10 professional baseball seasons when he briefly (three known games) suited up for the Monarchs in 1935. When Paige rejoined the Monarchs in 1939, he was a baseball leper, shunned by all teams for his role in dismantling the Pittsburgh Crawfords and refusing to report to Effa Manley’s Newark Eagles. In addition, he had hurt his powerful right arm in Mexico in 1938 and could no longer pitch effectively. When he returned to the U.S., a doctor told him he would never pitch again[1]. Wilkinson, a marketing genius, was the only one to take a chance on Paige. Paige joined the Monarchs in 1939, but not the “A-team.” Wilkinson assigned Paige to the Kansas City Travelers, the Monarchs development team, managed by Newt Jospeh. Wilkinson soon renamed the team the Satchel Paige All-Stars. While Paige’s pitching relied more on junk balls, the Paige name ensured the Travelers outdrew the Monarchs. Wilkinson then assigned Jew Baby as Paige’s personal trainer. Through a combination of salves, ointments, hot and cold baths, stretching, and massages, Floyd breathed life into Paige’s disabled wing, now believed to be a torn rotator cuff. The effects were wonderous. Over the winter of 1939-1940, Paige pitched for the Brujos de Guayama of the Puerto Rican Winter League leading the league with a 19-3 record, 1.93 ERA, and 208 strikeouts and was named the league’s MVP. Paige pitched for the Travelers in 1939 and 1940. By 1941, Paige had joined the Monarchs and was again rented out to other teams as an attraction for big games. Paige showed his loyalty to Wilkinson and appreciation of Floyd by eschewing his jumping from team to team until he received his call from the Cleveland Indians. The combination of Wilkinson and Floyd had extended Paige’s pitching career by 28 years and embellished his legend. Paige led Negro Leagues players into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971.

[1] Satchel Paige as told to David Lipman, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (The Curtis Publishing Group, 1961), 127.

Floyd became the first certified Black massage therapist and chiropractor in Kansas City opening the Floyd Center in the Lincoln Building, the same building housing the Monarchs offices. His private practice must have been thriving judging from the weekly ads he ran in The Call between 1940-1944. During this period, he continued his work with the Monarchs. The Call’s sports editor Sam McKibben credited Floyd for helping the Monarchs sweep the Homestead Grays in the 1942 Negro Leagues World Series by getting a bruised and battered Monarchs team out on the field. McKibben singles out catcher Joe Green and outfielders Ted Strong and Willard Brown as beneficiaries of Jew Baby’s ministrations and taping wizardry.

On the back of the card, Floyd is listed as 6’ 1-1/2” and 145 pounds.

Floyd continued with the Monarchs through the remainder of the 1940s and early 1950s. His last reported activity with the team came in June 1953 when he was listed as “Still on the Job” by The Call and now called “Doc” Jew Baby Floyd. “For years Jewbaby traveled with the Monarchs. Now he remains in Kansas City, but never misses being on hand when the club is at home.”

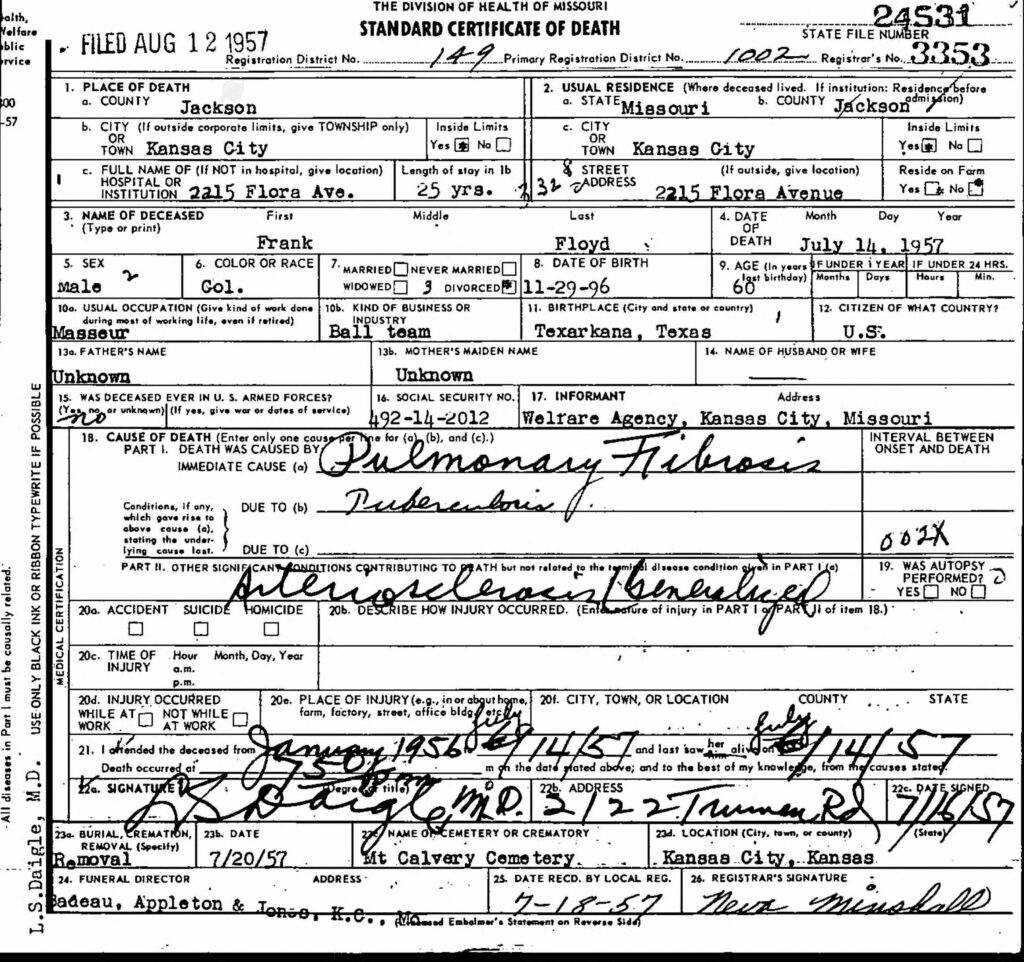

His health appears to have been in decline since the beating he suffered at the Louisianna prison farm. His last year with the Monarchs was 1954, but his death certificate recognizes his long service with the Monarchs listing his occupation as “masseur” and the industry as “ball team.” After a three-year illness, Floyd died of pulmonary fibrosis resulting from tuberculosis on July 14, 1957. He was buried in Mount Calvary Cemetery in Kansas City, KS.

Despite his long-life of service to the Monarchs, his end came alone. His obituary in The Call on July 26, 1957 states. “Jewbaby, once a pitcher, was with the Kansas City ball club before the name ‘Monarchs’ was given the team in 1920. This was in the days when the club was called the ‘All Nations’ club which was owned by J.L. Wilkinson. He attached himself to Wilkinson and the All Nations team shortly after he came to Kansas City from Texarkana in the early 1920s. For awhile he served as a pitcher and was regarded as a pretty fair chucker of baseballs.” He was buried with no public service and only the generosity of his ex-wife permitted his interment in a cemetery.

The Forgotten Monarch was the Monarchs longest serving employee. We can verify his employment beginning in 1923 and ending in 1954, a 32-year run. However, if the newspaper accounts are accurate, his run may have begun even earlier in 1920.

Graig Kreindler painting Frank James “Jew Baby” Floyd April 2024

The centennial 1924 Negro Leagues World Series card set featuring Ed Bolden’s Hilldale Club and J.L. Wilkinson’s Kansas City Monarchs contains a bonus baseball card (inserted one in every four sets) of “Jew Baby” Floyd based on Graig Kreindler’s painting. You may purchase both the set and the stand alone card at www.baseballartllc.com while supplies last.